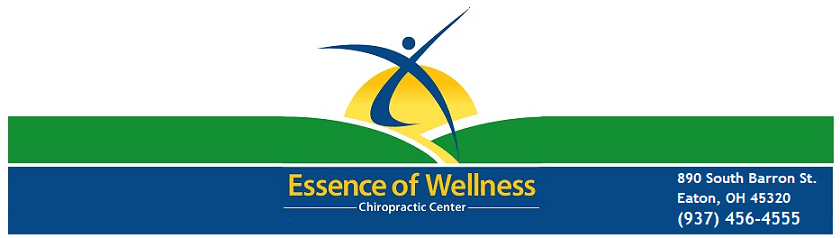

What are myofascial trigger points?

These are tender and tight spots within your muscles (Figure 1). Trigger points are linked to a condition called myofascial pain or myofascial pain syndrome (MPS). While MPS is commonly accepted among clinicians, there is still debate about how to define MPS and what causes it. Myofascial pain is prevalent and a frequent cause of visits to doctors and therapists. Unfortunately, few people live without ever having experienced muscle pain. This muscle pain results from such things as trauma, injury, overuse, strain, and prolonged postures to name a few. Much of the time, muscle pain may go away after a few weeks with healing of the tissues and other types of treatment such as stretching. However, pain will sometimes persist long after the injury. It may even refer to other parts of the body. For instance, neck muscles may refer pain to the head.

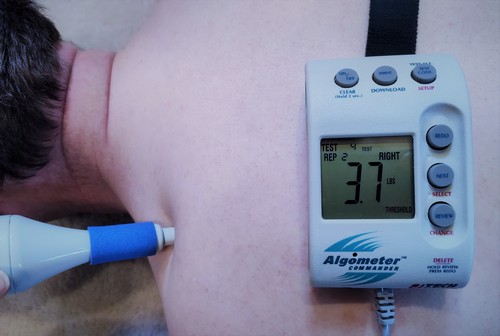

How are myofascial trigger points detected?

The most commonly employed clinical technique used to confirm the presence of myofascial trigger point is manual palpation – “hands-on” examination. Despite this, there is no consensus or validated guidelines that exist for the clinical diagnosis of MPS. Sometimes, practitioners will quantify your pressure pain threshold (PPT) which is defined as the minimum force applied which brings on pain. This can be determined with a pressure algometer (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Pressure Algometer

How are myofascial trigger points treated?

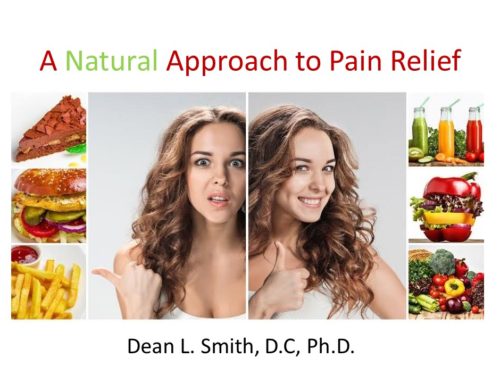

There are many ways to treat myofascial trigger points. Stretching the muscle can help, using a cooling spray on the skin before stretching the muscle can help, massage and pressure to the muscle along with stretching and manual therapy may provide further benefit. Other means to try to treat trigger points include transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) which administers electricity via pads applied to the skin, acupuncture, ultrasound, low level laser therapy, dry needling, and injections with various types of medication. One should also try to find the reason for the appearance of trigger points to try to prevent them from recurrence. Perhaps sustained postures may be contributing or nutrient deficiencies, or an inflammatory diet, or workplace ergonomics. See this video for ways to try to reduce pain naturally.

Self-care for myofascial trigger points

Common strategies for working on trigger points include using foam rollers, massage devices including rolling massage, balls and other instruments. The science behind these strategies is emerging and even though these strategies are used frequently in clinical practice, it is important to realize that there is limited evidence especially for pain reduction. The tools are often used to:

- increase range or motion (ROM)

- decrease myofascial pain

- improve recovery from exercise-induced muscle damage

- improve performance

I will concentrate on the use of balls as trigger point tools in this article for a few reasons – cost, ease of use and available evidence. In the office, we frequently recommend the use of balls due to these factors. Various types of balls can work depending on your pain level, comfort and tolerance (Figures 3-4). You can use a single ball on one trigger point or use a sock to link two balls together which may be useful for example to span across sides of your lower back. My preference is a simple tennis ball for most people. A tennis ball is suitable for treating muscle or fascia on a smaller surface area. Smaller balls may also be more versatile than a foam roller since the balls can concentrate on a focal spot as well as work in a three-dimensional mode.

Figure 3. Types of balls commonly used in myofascial self-care.

Figure 4. Tennis balls in a sock.

Use of a ball for self-myofascial care can include constant pressure, varying pressure or rolling over the trigger point vertically or horizontally. As a general rule, instructions for constant pressure on the trigger points are usually to be just under the threshold of pain. When people are in pain, this many not be possible, so I’d ask your chiropractor about an appropriate pain level. The time of compression can vary from 15 seconds to one minute, with about 90 seconds between sets. Starting out, I’d recommend 5-10 seconds at a time then building up as tolerance allows. Two to three sets are fairly typical.

Self-myofascial care also frequently involves making small rolling movements (undulations back and forth) over balls or foam rollers. Sometimes the undulations are concentrated over the painful area of the muscle. The small undulations place direct and sweeping pressure on the soft-tissue which is believed to cause a warming of the fascia, breaking up soft tissue adhesions between the fascial layers and hopefully restoring soft-tissue extensibility.

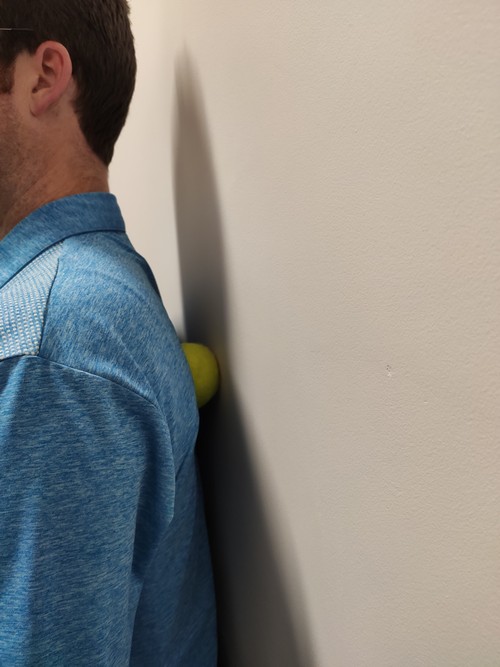

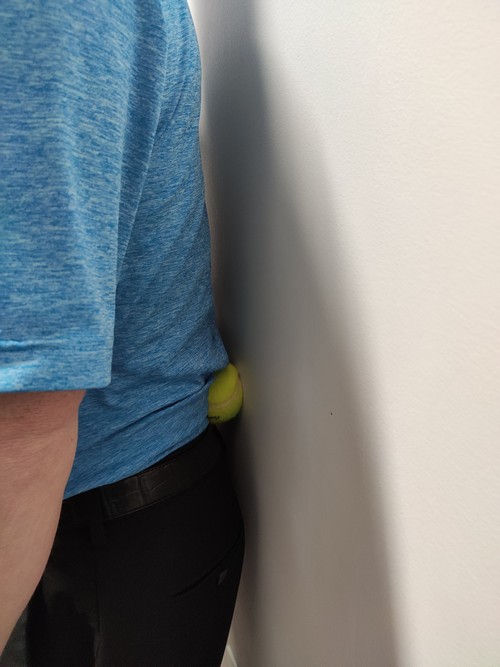

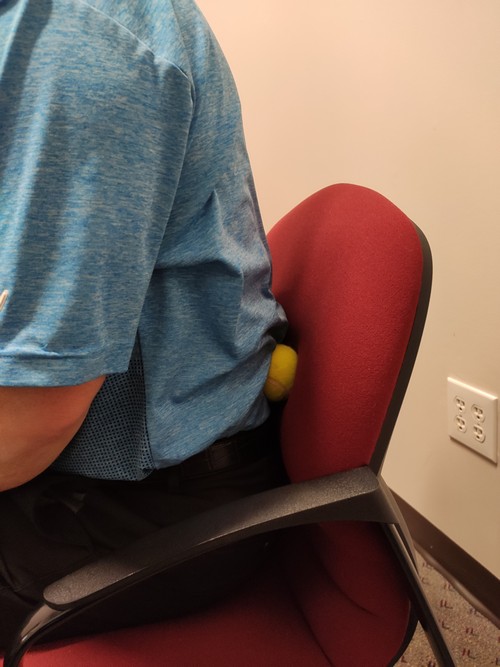

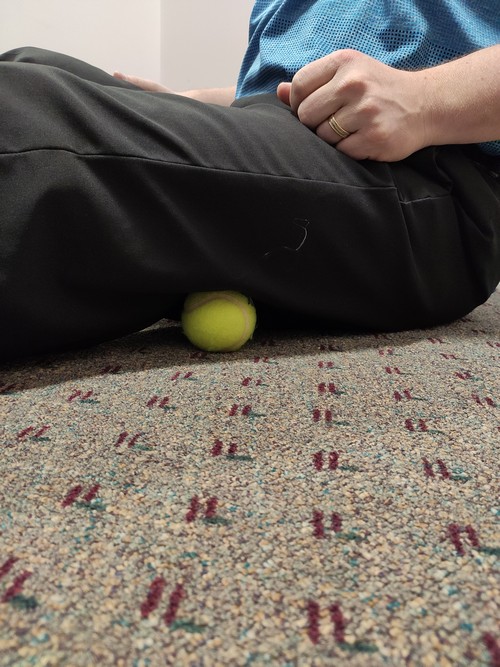

Below are some of the common locations your practitioner might recommend you use a ball for self-myofascial care (Figures 5-16). Note that there are different postures and positions that can be adopted. Standing, seated and lying down postures are good ways to do both compression and compression with small rolling movements. Giving yourself a hug is a way to expose more back muscle to the tennis ball because it gets the shoulder blade out of the way.

Figure 5. Suboccipital muscles

Figure 6. Left and right suboccipital muscles with sock

Figure 7. Upper trapezius muscle

Figure 8. Rhomboid muscles

Figure 9. Rhomboid muscles with hug

Figure 10. Lower back muscles

Figure 11. Lower back muscles seated

Figure 12. Buttock muscles

Figure 13. Hamstrings seated

FIgure 14. Hamstrings on ground

Figure 15. Iliotibial band

FIgure 16. Plantar fascia

References:

| 1. | Effect of self-myofascial release on myofascial pain, muscle flexibility, and strength: A narrative review. |

| Kalichman L, Ben David C. | |

| J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2017 Apr;21(2):446-451. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.11.006. Epub 2016 Nov 14. Review. | |

| PMID: 28532889 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 2. | Is self myofascial release an effective preexercise and recovery strategy? A literature review. |

| Schroeder AN, Best TM. | |

| Curr Sports Med Rep. 2015 May-Jun;14(3):200-8. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000148. Review. Erratum in: Curr Sports Med Rep. 2015 Sep-Oct;14(5):352. | |

| PMID: 25968853 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 3. | Pressure pain thresholds of tender point sites in patients with fibromyalgia and in healthy controls. |

| Maquet D, Croisier JL, Demoulin C, Crielaard JM. | |

| Eur J Pain. 2004 Apr;8(2):111-7. | |

| PMID: 14987620 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 4. | Do Self-Myofascial Release Devices Release Myofascia? Rolling Mechanisms: A Narrative Review. |

| Behm DG, Wilke J. | |

| Sports Med. 2019 Aug;49(8):1173-1181. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01149-y. Review. | |

| PMID: 31256353 [PubMed – in process] | |

| Similar articles |

| 5. | Myofascial Pain: Mechanisms to Management. |

| Fricton J. | |

| Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2016 Aug;28(3):289-311. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2016.03.010. Review. | |

| PMID: 27475508 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 6. | Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Narrative Review Identifying Inconsistencies in Nomenclature. |

| Phan V, Shah J, Tandon H, Srbely J, DeStefano S, Kumbhare D, Sikdar S, Clouse A, Gandhi A, Gerber L. | |

| PM R. 2019 Nov 17. doi: 10.1002/pmrj.12290. [Epub ahead of print] Review. | |

| PMID: 31736284 [PubMed – as supplied by publisher] | |

| Similar articles |

| 7. | Fibromyalgia and myofascial pain syndrome: Two sides of the same coin? A scoping review to determine the lexicon of the current diagnostic criteria. |

| Bourgaize S, Janjua I, Murnaghan K, Mior S, Srbely J, Newton G. | |

| Musculoskeletal Care. 2019 Mar;17(1):3-12. doi: 10.1002/msc.1366. Epub 2018 Oct 23. Review. | |

| PMID: 30350334 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 8. | A soft massage tool is advantageous for compressing deep soft tissue with low muscle tension: Therapeutic evidence for self-myofascial release. |

| Kim Y, Hong Y, Park HS. | |

| Complement Ther Med. 2019 Apr;43:312-318. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.01.001. | |

| PMID: 30935551 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 9. | Self-Myofascial Release of the Superficial Back Line Improves Sit-and-Reach Distance. |

| Williams W, Selkow NM. | |

| J Sport Rehabil. 2019 Mar 12:1-19. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2018-0306. [Epub ahead of print] | |

| PMID: 30860410 [PubMed – as supplied by publisher] | |

| Similar articles |

| 10. | Effects of Self-Myofascial Release on Shoulder Function and Perception in Adolescent Tennis Players. |

| Le Gal J, Begon M, Gillet B, Rogowski I. | |

| J Sport Rehabil. 2018 Nov 1;27(6):530-535. doi: 10.1123/jsr.2016-0240. Epub 2018 Sep 30. | |

| PMID: 28952852 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 11. | A pilot study of balance performance benefit of myofascial release, with a tennis ball, in chronic stroke patients. |

| Park DJ, Hwang YI. | |

| J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2016 Jan;20(1):98-103. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.06.009. Epub 2015 Jun 25. | |

| PMID: 26891643 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |

| 12. | The immediate effect of bilateral self myofascial release on the plantar surface of the feet on hamstring and lumbar spine flexibility: A pilot randomised controlled trial. |

| Grieve R, Goodwin F, Alfaki M, Bourton AJ, Jeffries C, Scott H. | |

| J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2015 Jul;19(3):544-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2014.12.004. Epub 2014 Dec 18. | |

| PMID: 26118527 [PubMed – indexed for MEDLINE] | |

| Similar articles |